Nudge Science: Removing obstacles & making it easier for a desired change to emerge

I’ve been obsessed with what fosters creativity, innovation and real systems change for a long time. My obsession and curiosity led to a graduate thesis on what foster’s relevant creativity as well as the development of Think Jar Collective where creative collisions can emerge. At the root of much of this work is a desire to spark and steward meaningful change. Change sometimes from a stiff, status quo state to a more flexible, inclusive, innovative system state. A need for a change often comes from feedback loops and sometimes from brave minds with wicked good pattern recognition, who see a challenge, a problem, an opportunity and just have to figure out a way to make a situation better. As we all know, change within ourselves is hard, but when trying to shift change in services, systems, and minds other than our own, the complexity is only intensified. There have been interesting counter intuitive developments around change making in the last 15 to 20 years. One of these is Nudge Science and it’s an intriguing set of ideas worth knowing a bit about and exploring if you’re an innovator, change maker, or someone trying to shift behaviours of systems to be more humanized and better.

How Does A Change Happen?

How a positive change is catalyzed, of course depends on what type of change we’re striving to make and what our definition of a proposed change is. If we’re focused on shifting behaviour of individuals, or groups that make up systems, then there are some interesting patterns from history to learn from.

The late cognitive scientist Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking Fast and Slow(2011) shared a really intriguing idea around how behaviour change generally happens in human minds and systems. Basically he says that when trying to elicit a change, human beings throughout history have tended to rely on only three types of approaches- threats, incentives and arguments. However, more recently and accelerated by digital innovation, there have been a few new catalysts for change that have come on the scene. Kahneman believed that after the long history of the 3 types of change approaches, one of the most important ideas in modern behavioural psychology arose from the work of Kurt Lewin. The idea from Lewin is around enabling a desired behaviour change to be easier rather than harder. Why? Because reducing stressors, noise and complications for a desired change will make the change stickier and more sustainable. In a podcast a number of years ago, Kahnman summed up the idea in the following way,

“Kurt Lewin developed one of the most interesting ideas in modern psychology when he studied what changes behavior. Rather than arguments, threats or incentives, he asked a very different question. He asked, why aren’t people going to the desired change by themselves? What is preventing people from going on their own? And then remove obstacles. In other words, How can we make it easier to go towards the desired positive change?” Daniel Kahneman on the Sam Harris Podcast, episode #150

Enter Nudge Science

Just a little nudge will do it

Building on Lewin’s ideas, some have called designing easier change pathways Nudge Science. In the book Nudge – Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (2008), Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein suggested that if a particular behavioural or decision making pattern is the result of cognitive boundaries, biases, or habits, this pattern may be “nudged” toward a better option by making choices easier through redesigning choice architecture in a system.

“A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.” (Thaler & Sunstein 2008, p. 6)

So, as a simple example, if you want kids to change their behaviour to eat healthier foods, then try placing bowls of fruit and veggies in easy to see access areas, rather than junk food as the easily accessible option.

“But some people and systems don’t deserve easy change”

These ideas from Lewin and Kahneman have been compelling for me, but also they have sown cognitive dissonance and discomfort. For me, when I think of making a digital user interface more intuitive to navigate, I can get behind this notion of making a desired user behaviour easier. But, when I think about a person, or group or system that I think needs to change their values, and behaviors from their current state, then if I’m honest, I kind of don’t want it to be easy. This was a hard realization to come to and took a long time to uncover that in certain kinds of change making innovation, my ego is entangled and wants some people and systems I have maybe labeled as “oppressors” to have a hard time before they are allowed to have it easy. But, is making change hard-almost out of punishment, helpful for the desired change? Or have my moral sensibilities to make change hard for some, blinded me from seeing the big picture and unintentionally blocked real change possibilities? In many of the social change and policy innovation spaces, making change hard for some I have seen as a covert value and all too common practice, especially in the last 10 years. We talk a big talk, threaten and argue on the side of “righteousness”, and hope others will change from that. But rarely does any person or system make positive lasting change from fear, shame, or punishment. In fact, studies are showing, these oppressor/oppressed binary values in change making are likely contributing to division, polarization, and not leading to more freedom for the oppressed. It’s a bit frustrating, but if we really want to be a positive part of stewarding relevant system and social change, we probably need to follow the brain science on making change easier. Grappling with these tensions, check out some of the work colleagues and I co-stewarded in Shift Lab 2.0 where we experimented with Nudge Science as an innovation in Anti-racism systems change work. This work resulted in very interesting prototypes and one particularly impactful initiative that is now scaling called You Need This Box: YNTB is an innovative anti-racism learning subscription box that a community team created, tested and are growing. It has the principles of making behaviour change easier by sending participants learning gift boxes that have curated private activities to explore and builds in multiple learning touch points over a year. Having multiple small learning touchpoints were designed because real change doesn’t happen from a one day training event, but more from little moments of reflection, and nudges over time.

Check out the Nudge Principles we researched and integrated in our Shift Lab Behaviour Change Card Deck

The Dark Nudges

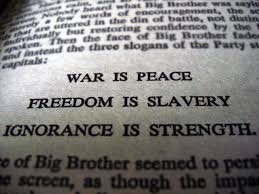

From George Orwell’s 1984

It’s important to acknowledge that there is also a dark side to Nudge and Behaviour Change Science. No matter how smart we think we are, we are all susceptible to our brain’s blind spots and conformist social habits that help us not always be in conflict with others as we navigate the world. These and other blind spots can be taken advantage of and shockingly we might discover one day that even our beliefs and values can be changed without our consent or awareness. Most of these dark nudges are designed to make us buy something or to keep our attention with a platform, or brand. At their worst, the dark nudges are lies engineered to bombard our emotions and blind spots. Often bombarding us through media and digital platforms we interact with daily. If someone tells us a lie enough times, we are likely to believe it because our brains evolved to believe more in false positives. Having a default to believe in false positives is why repeated lies can work so well to change minds, values and beliefs in society. Our default whether we like it or not is to believe what we see and what people tell us. It takes more energy in our brains to question, and critically analyze. George Orwell, comically-but kinda not comically, pointed to this problem of how easy it is for us to fall for the default to believe and conform. In his masterpiece of fiction, 1984, that is unfortunately more and more resembling current reality of 2024, the Ministry of Truth pushed out slogans to stop dissent, and keep society numb and in line. These slogans were kind of Dark Nudges like, “War is Peace” “Freedom is Slavery” and “Ignorance is strength” repeated over and over again. Hopefully these fictional slogans seem absurd to you, but if our society was repeating them enough and our friends and family began to wonder if there might be some “truth” to them, then they could become shared belief. Don’t think you’re too smart for that to happen. We all can fall for it and the digital platforms we interact with daily are shaping choice architecture, our preferences, and desires in ways we have never known in human history. We have to be more aware and innovation in regulation is likely needed. There are non-profits like the Center for Humane Technology (CHT) who are working against the intentional and unintentional Dark Nudges. CHT is dedicated to radically reimagining digital infrastructure. Its mission is to drive a comprehensive shift toward humane technology that supports collective well-being, democracy and a shared information environment. The main tools at present to combat the dark nudging is to draft legislation on data transparency, data sovereignty, and education. Learn more on what can be done here. But there is still some good in the Nudge Science worth harnessing.

A case study in Nudge Science for good: MyCompass Planning

A support worker and client using MyCompass Planning

MyCompass Planning is a digital social service case management tool on a mission to humanize social service interactions, care planning and social service architecture. I’m one of the co-founders and originally saw the innovation and systems change opportunity. The nudge science principle integrated throughout the MyCompass platform is around making it easier for support workers, administrators and policy makers to focus on the strengths and rights of those they serve. In the early R&D phase we wondered, What If We Focused on Removing Barriers and Designed Ways That Might More Naturally Bring Out Empowering Social Service Interactions?

There is a lot of good in social services and a lot of not so good in terms of many social service delivery systems being built more for the needs of policy makers and administrators and not for the actual people meant to be served. A lot of social services are hard for people in service to understand and are often not as helpful as us administrators would like to believe. For years the way of humanizing these social service systems, was through rights based arguments, sometimes threats and sometimes incentives. Changing minds, values, policy and service interactions to act on valuing marginalized folks more, is a very hard thing to do in a way that actually shifts behaviour of people and systems. But threats, arguments, and incentives is all we had really known until we collided with Lewin, Nudge Science and a fly in a urinal.

Weird creative collisions

Before the design and nudge science I was more of a one sided true believer in social justice ideas of Paulo Friere and the notion that freedom is not given but can only be taken. Admittedly, I was into the idea that the world can be divided up into binaries of oppressor and oppressed. This meant I used well intended threats and a bit of anarchy in my youth to try to make positive social change. I believed these approaches were the moral way to support marginalized folks to get out from underneath oppression. And sometimes, in some extreme contexts, those approaches are still needed, but in most situations at present, more nuanced change making is needed.

“Freedom is acquired by conquest, not by gift” Paulo Freire

Quote from the author on the seeds of MyCompass from an article on Social Innovation by the McConnell Foundation

The thing that eventually became clearer, is that all of us humans are caught in our biases, ideas and stories. Since we are all caught, the oversimplified binary boxes and labels don’t really fit in the complex world we inhabit together. Within that rigid self-righteous mindset and context, a weird creative collision happened almost 15 years ago that jarred loose new perspectives and led to MyCompass.

The idea for what became MyCompass Planning, came one day when I heard a famous designer at a conference at Pixar talk about how we need to stop designing objects that ask us to change(arguments, threats), and start designing behaviours and interactions that bring out the change. The designer gave an example about how at an airport in Amsterdam, someone decided to print a little fly in urinals to see if it might reduce the mess that happens in men’s washrooms. For some unknown reason deep in men’s brains, men would consistently aim at the fly and this shift in behaviour would result in consistently reducing the mess in public bathrooms by 80%- All done without threats, incentives or arguments. Maybe due to being frustrated with the tools of social justice not really yielding impactful change, or maybe because I was consciously seeking out ideas in domains very different from where my mind was at, something connected from the weird urinal story and sparked an obsession to think differently about change making in the social services space.

What’s the equivalent of a fly in a urinal to nudge social services to be more empowering?

“Creativity is connecting the seemingly unconnected” William Plommer

Image: Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” /urinal that rocked the status quo in the art world in the early 1900s.

Lewin, the fly and the urinal made me wonder what might be the equivalent of a fly in a urinal to shift interactions in social services so that they more honestly focus on the strengths of people served, and don’t just help people survive but launch people to thrive? Over time, about a million dollars of scrappy R&D and co-design with people served and administrators, MyCompass created tools and service interactions that make it easier for social service agencies to re-center around people served while at the same time getting organizational needs met.

MyCompass did this by creating interactions and mechanisms that nudge support workers to focus on the real person they are serving. These nudges remove obstacles so systems can’t continue to see and relate to people as simply case file numbers, deficits and challenges to “fix”. For example, case notes are necessary for social service reporting, however, existing systems are unintentionally set up to cause support workers to focus on deficits and challenges in their notes. With MyCompass, we designed a log note feature that captures not only more traditional notes (e.g. critical incidents, medication administration) but also spurs support workers to engage in empowering conversations with people served and provides ways to visually document and reflect on important things that happen in a client’s day. This means the service interaction of reporting brings out humanizing interactions, story telling, and reflection that centers the voice of people served, not just the voice of social service workers and administrators. Ultimately these humanizing interactions celebrate more robust inclusion and help support workers and people served to swap “good enough” interactions for interactions that are empowering. People served gain new power to be at the helm of cultivating their best life, with support workers, family and allies right alongside. Nudge by nudge, service delivery systems re-center around the unique needs and aspirations of each person served to redefine authority flows and humanize the social service architecture. We’re just at the beginning and feel there is still so much potential for systems change and innovative R&D around designing easier and more ethical service interactions through MyCompass.

Too much to read and you had to skip to the summary? Here you go.

Humans have not innovated much around change making throughout history. For most of our time we have only used Threats, Incentives and Arguments to try to make change.

Nudge Science is an innovation in change making and is about removing behavioural obstacles and making it easier for a desired change to come about.

We need to deal with our biases that in some complex social change spaces we don’t like the idea of making change easier for some people and systems because it doesn’t feel fair. Be careful if inherent in the change you want to bring about, you have a self-righteousness bias that does not want to make a change easier for some. Why is that?

There is a dark side to Nudge science when bad actors take advantage of blind spots in our brains. This is happening more through digital platforms now and lots of policy and tech regulation is likely needed

Nudge science for good requires transparency, consent, and should be about making it easier for a collective good to emerge.

MyCompass Planning is a case study in creatively applying nudge science to social service redesign.

Seek creative collisions in unexpected places and domains if you want innovative ideas to emerge.